Volume Weighted Average Price (VWAP)

Institutional firms rely on VWAP to execute large orders (millions or billions in value). They break down orders into smaller pieces and use VWAP to ensure executions occur at a fair price without significantly impacting the market.

Used by: J.P. Morgan, Morgan Stanley, RBC Capital Market, Jane Street, BlackRock

[1] J.P. Morgan U.S. Quarterly Summary

[2] Morgan Stanley’s U.S. Cash Equity Order Handling & Routing Practice

[3] RBC Capital Markets Aiden® Arrival Announcement

[4] ETF Execution Strategies — A study note on Jane Street’s Report

[5] BlackRock Global Perspective White Paper

To understand why VWAP is useful, it helps to look at its connection to statistics, specifically the Central Limit Theorem (CLT). The CLT states that as more data points are collected, the average of those points becomes a reliable estimate of the true mean. In trading, this means that as the number of transactions increases throughout the day, the volume-weighted average price becomes a strong indicator of a fair market price.

VWAP continuously updates from the market open, calculating an average price weighted by the volume of trades. Larger trades have a bigger impact on VWAP, while smaller trades influence it less. This makes VWAP a better measure of fair value than a simple moving average, which treats all prices equally regardless of volume. Since VWAP resets daily, it reflects the trading activity of the current session and does not carry over past data.

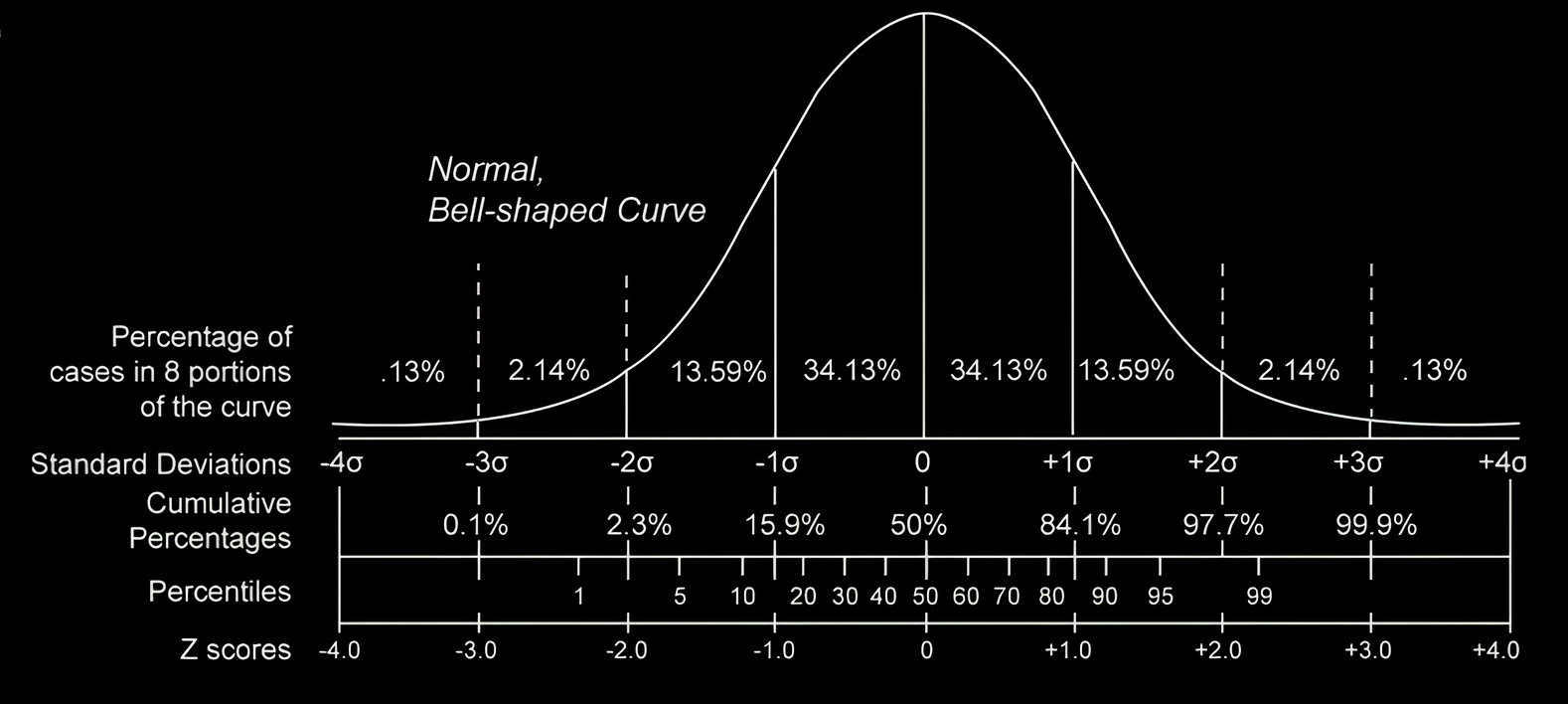

In trading, prices tend to revert to the mean over time, and VWAP serves as a dynamic reference point for this mean. This concept is rooted in statistical probability, particularly the normal distribution, often visualized as a bell curve. Throughout the trading session, short-term price fluctuations may push the market significantly above or below VWAP. However, much like how values in a normal distribution cluster around the mean, price movements often stabilize around VWAP as buying and selling pressures balance out.

When prices move too far from VWAP—especially beyond two or three standard deviations—it often signals an overextended market. Institutional traders and algorithms recognize this, leading to increased buying when prices are well below VWAP and selling when they are well above it. This behavior naturally pulls the price back toward VWAP, reinforcing its role as an anchor. While this mean-reverting tendency is strong, it is not absolute. In strong trending markets, price may stay above or below VWAP for extended periods. However, in range-bound conditions, VWAP serves as a powerful magnet, drawing prices back toward it as the day progresses.

Traders often use standard deviation bands around VWAP to gauge price extremes. These bands act as dynamic support and resistance levels. As illustrated in the graph, the six bands represent distances of 1, 2, and 3 standard deviations from the Volume Weighted Average Price (VWAP).

1 Standard Deviation (68% Confidence Interval): Represents normal price fluctuations.

2 Standard Deviations (95% Confidence Interval): Indicates potential overbought/oversold conditions.

3 Standard Deviations (99.7% Confidence Interval): Signals extreme price movements, often leading to mean reversion.

The chart above illustrates AMD's price action on NASDAQ on January 25, 2025. The price initially reversed after reaching the second standard deviation upper band, then bounced back after hitting the second standard deviation lower band, before reversing once more upon touching the upper band again.